Theophilus Thompson’s Thumbnails

Dr. Steven Dowd sent this piece earlier in the year as a follow-up to his instructive “Anticipation” essay he did on Theophilus Thompson. These two stories “sandwiched” Neil Brennen’s work on Thompson and adds to the intrigue of this pioneer of American chess history. Of course he is more of a pioneer to the Black population. He may be the first player of African descent to make a lasting impact on chess.

While it should not matter that these contributions have come from outside of the African Diaspora, it should provide motivation for people of African descent to delve deeper into the history of Mr. Thompson and other uncovered history of other pioneers. We owe a debt of gratitude to Dr. Dowd and Mr. Brennen for giving these works the exposure and respect they deserve and hope that these exercises will be models of excellence for centuries to come.

~Daaim Shabazz, The Chess Drum

by Steven B. Dowd

I again want to thank Dr. Shabazz for letting me use the well-respected pages of The Chess Drum for my critiques of Theophilus Thompson’s problem output. To date, only Walter Korn, in his America’s Chess Heritage (McKay, 1978), has made any attempt to look at his problems. That problemists and problem authors avoided him is perhaps understandable – until it became available in electronic form, his book was extremely hard to find, and he was a shooting star of chess – here one day, and then, mysteriously gone. But there are other American problemists in similar situations who received their due in old and modern magazines, whereas only Korn seemed to care to discuss Thompson.

.jpg)

Theophilus Thompson’s book, “Chess Problems” published in 1873.

His Best Two-movers

Theo’s (I hope it isn’t presumptuous to call him that) mates in two were composed in the days when a snappy key and nice mates sufficed for a good problem. It would take the formation of the Good Companions by James Magee in 1913 before the American two-mover became thematic and task-oriented, and the problem became even less connected with the practical game. That is not necessarily a deficit. You can consider the game a work of non-fiction and problems work of fiction, often fantastic fiction. Players who decry problems with the lament, “But that could never happen in a real game!” don’t realize how hollow their words sound.

But Thompson’s two-movers, composed before themes and cycles and so on became fashionable and showing simple strategy in an appealing form, may be considered more enjoyable by the modern player. Besides the theme known as a Y-flight, which we saw in my first article, this are no problems with a theme in his book, but that again, is not unusual for that day and age. The following problem shows a line clearance similar to the Bristol theme; it is not an actual Bristol as in that theme, the line-clearing piece must have no subsequent function in the problem. For a really nice discussion of the Bristol, see Emmanuel Manolas‘ page.

White to Play and Mate in Two

[FEN “8/8/5b2/1k6/1P6/1K6/6B1/7Q w – – 0 1”]

So how do we clear a line? The only way is by sending the bishop to the far corner of the board with 1. Ba8! There it will support mates by Qc6 and Qb7 (the threats). If you want problems to help you in your OTB chess, letting that piece of fiction guide you in your own non-fictional games, consider the role of the Bf6. Found it? For one, it prevents 1. Qh7! Which has the same idea of mating on b7, making any sort of line clearance unnecessary.

Another popular set of themes are those involving interference, where a piece places itself on a square where it may be captured; the Novotny is the best known of these. Here is a problem with a simple one piece interference.

White to Play and Mate in Two

[FEN “7K/8/6N1/5b2/1nR5/3p1k1B/8/6Q1 w – – 0 1”]

The key is the visually appealing rook sacrifice 1. Re4! 1. .. Bxe4 (interfering with the king’s flight) 2. Bg4#; 1. .. Kxe4 Bg2#, and on other moves 2. Qg2#, 2. Re3#, or 2. Qe3# follow. If you don’t follow problems, you may be amazed to know that the fact that the move 1. Re4 sets up a triple threat, and is thus considered a weakness of the problem. Today, setting up multiple threats typically requires differentiated mates, as in the popular Fleck theme. Another weakness is that the interference move is not pure, meaning that it not only deflects the bishop, taking a flight from the black king, it also removes the guard from g4.

These critiques, of course, come from 21st century hindsight and the view of a 21st century problemist. They should not be considered as any sort of denigration of the great work Thompson did.

Thompson used the geometry of the board well in his problems, and as noted, liked sacrificial and snappy keys. This is one of my favorite of his “twoers.”

White to Play and Mate in Two

[FEN “Q6K/4N3/3p4/2pBk1B1/8/8/1R5N/7q w – – 0 1”]

The unprovided set check 0. .. Qxh2+ would be considered a deficit today. By unprovided set check, it means Black has a check in the position, and were it his turn to move, he could destroy White’s mate in two with that move. But in those days….

The key is the exceptionally attractive corner-to-corner 1. Qa1!, sacrificing the queen for control of the f3 square, and threatening a shut-off mate of 2. Rb1# (as well as, unfortunately again, 2. Re2#. In addition to the multiple threats, it would be nice if these mates could somehow be differentiated; that is, only occur under certain black defenses). 1. .. Qxa1 2. Nf3#; 1. .. Qxh2+ 2. Rxh2# (a discovered cross-check); 1. .. Kd4 2. Rd2#

This next problem is quite likeable, even though it takes two flights from the black king with the underpromotion key.

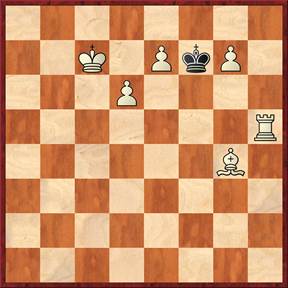

White to Play and Mate in Two

[FEN “8/2K1PkP1/3P4/7R/6B1/8/8/8 w – – 0 1”]

Since White has to mate in two, he can’t let the king out of the box, so 1. e8=N!. If he takes the knight with 1. .. Kxe8, he is mated with the “big promotion” 2. g8=Q#, and if he tries to escape to g8, 2. Be6#.

This is the last problem to make the cut. Line-openings and closings with pawns can be attractive in two-movers. Here the key can be found if you find the potential line-opening that would get the king an escape route.

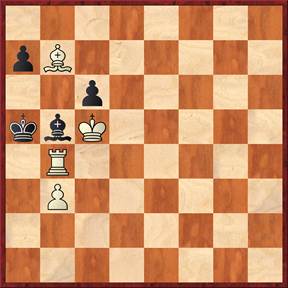

White to Play and Mate in Two

[FEN “N2b3R/3Kp3/4P2p/p2k4/1pp1pP2/8/N4B2/R2B4 w – – 0 1”]

If you surmised that Black is threatening to escape with ..e3, allowing ..Ke4, you will see the key, and the possible continuations: 1.Be3 a4 2.Nxb4#; 1…b3 2.Nc3#; 1…c3 2.Bb3#, 1…h5 2.Rxh5#; and then, if the bishop moves, 1…Bc7 2.Nxc7#; 1…Bb6 2.Nxb6#.

The Mystery Problem

This is a problem by Thompson that appears in the major chess problem databases. Initially I could not find the problem in my copy of his book. It is also a terrible problem in my opinion and I preferred to believe it was not his.

White to Play and Mate in Two

[FEN “8/pB6/2p5/kbK5/1R6/1P6/8/8 w – – 0 1”]

This sacrifice of the rook, followed by the mate with the pawn, had been used before, and has been used since in various problem types. The key is 1. Ra4+! And then on 1. .. Bxa4, 2. b4#. It’s not especially well-constructed (why the black pawn on a7?)..But every problemist has a few “freshman efforts” and this is obviously one of his.

So How Does He Stack Up?

As a beginner to chess problems, Thompson, with his one-year output, looks quite talented. But how do his problems stack up overall against others from this time period? Let’s look at what were probably the two best American two-movers of the 1870s, both cited in Kenneth Howard’s One Hundred Years of the American Two-Move Chess Problem (Dover, 2nd. Ed, 1962). The first was probably familiar to Thompson, and the second appeared after his short career ended.

First Prize, Dubuque Chess Journal, 1871

White to Play and Mate in Two

[FEN “BRK5/8/8/3N3p/1Q5B/3kp3/N3p1R1/8 w – – 0 1”]

Here White makes an immediate battery formation with 1. Qd6!, and the mates are differentiated based on the movement of the king; 1. .. Kd2 2. Nbd4#; 1. .. Kd4 Nb6#; 1. .. Ke4 2. Ne7#; 1. .. Kc4/2 2. Nxe3#. The pawn on h5 stops the cook 1. Be1. George Carpenter was 11 years older than Thompson, and had a wealth of experience composing before this first prize; I have no doubt that Thompson could have composed something as good, if not better, had he continued to compose.

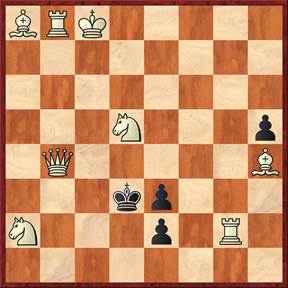

First Prize, Huddersfield College Magazine, 1877

White to Play and Mate in Two

[FEN “8/3p1p1Q/1K2k3/1N1Np3/8/1B6/8/8 w – – 0 1”]

William Shinkman and Thompson had played a correspondence game in 1875; you can see the game here in Neil Brennen’s article on Thompson (Shinkman also won that tournament). Shinkman, born in Bohemia, became the United States’ best problemist of his long career; there are a few who rate him even ahead of the great Sam Loyd.

Back to the problem: Here White gives up his battery with 1. Ba4! d6 2.Nbc7#; 1…e4 2.Qxe4#; 1…Kxd5 2.Bb3#; 1…f5 2.Qg8#; 1…f6 2.Ndc7#. This is a great problem that would be publishable today, and has an interesting story surrounding it. Carpenter also composed a very similar problem that was published later in the month. The exception was that his had a superfluous pawn on e7. Thus Shinkman gets credit for this one by a hair; even though Carpenter’s was inferior to Shinkman’s, had Carpenter’s problem been published first, he would have been able to claim authorship.

Conclusion

Based on his small output, Thompson would probably be considered an average two-move composer for his day. He certainly was composing at least as well as his “teacher,” J.K. Hanshew, in that domain. I place teacher in quotes as Hanshew was mainly a guide, providing Thompson with source material more than tutelage. Thompson certainly understood chess aesthetics better at that period of his development than I did. It’s impossible to ascertain how far he could have gone but it seems fairly certain he would have won at least a few informal tournaments had he continued composing.

The mystery of the terrible problem is that I am a terrible historian!

But for budding scholars who hope not to follow my route: I relied on an electronic edition with pages missing, and having finally secured a printed edition of the book, I realized my mistake. It is one of his; the kind of freshman effort all of us problemists make. But instead of verifying, I assumed. Sigh.

I’ll ask Dr. Shabazz to leave my little mistake up for awhile, so that all can see and then quietly have him revise the article. I am sure Mr. Winter is already revoking any tenuous hold I ever had on being a chess historian.

Just give me whatever changes you have. I’m sure it’s not much.