Book Review: Chess Behind Bars

Chess is often thought of as a game of the high-browed intelligentsia. It has adherents worldwide and is touted as an activity to sharpen one’s mind and to enhance cognitive ability. Does chess really make people smart? No, but it can certainly help the mind stay sharp and teach valuable lessons about patience and decision-making. It comes as no surprise that the game has become one of the most popular inside correctional institutions around the world. There is so much intrigue about prison chess that many volunteers seem to relish a chance to play these self-taught chess sharks.

Carl Portman of England released a book last year titled Chess Behind Bars, a poignant look at chess in British prisons. The book serves as part-instructional guide with some powerful testimonial statements made. The book starts with a Foreword by GM Nigel Short who described the contact he maintained with an inmate even after his release!

“Carlton has repeatedly said how important chess was to him during these very dark times, allowing him to focus on an enjoyable and intellectually stimulating pursuit, while the shadow of never-distant depression hung about him. He still treasures the Yugoslav-produced Chess Informant – the bible of the pre-computer age – that I gave to him then.

There have been a number of personal stories and I have written a few here at The Chess Drum confirming the impact that chess has had on inmates. In fact, I have also had contact with inmates over the years and have sent books and other literature. The only issue is that inmates often began to ask for other items such as legal books and requests to contact relatives.

Oftentimes it is difficult to get cooperation from prison officials. In one case, materials sent to a prison in New York were returned citing “codes throughout” as if it were a secret message to the prisoner. I’m not sure if the official was serious about the ignorance or was simply being difficult. Portman affirmed this…

One of the most attractive aspects of chess is that it is available to everyone. However, just because the game is available does not mean that everyone is able to reach out and embrace it. Prisoners are certainly one such group. For various reason some prisoners cannot obtain chess sets, books or magazines. This may been understandable in 1940s Russia, but here – in Britain in 2017? Surely not?

Portman’s stirring preface does about as good a job as I have seen to market chess as a reformative tool for inmates. The data backs him and chess in prisons have received some buzz in England and other countries. We have heard of chess being used as a metaphor for life in cinematic portrayals.

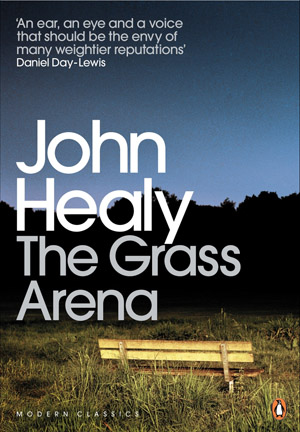

The Grass Arena is one such movie. It was adapted from the autobiography of John Healy, a former alcoholic who was taught chess in prison. He gives a lengthy interview in the book. Another is Life of a King starring Cuba Gooding who played Eugene Brown, an ex-inmate who founded the “Big Chair Chess Club” and used chess to reach rowdy youth.

Many prisoners attempt to reflect on their lives and the decisions they have made. Chess can help one to externalize thoughts and to examine them. Issues such as impatience, impulsiveness, over-aggression all can be seen and analyzed in a constructive way through chess. Portman obviously believes that chess can make a difference in “redemption.”

Portman’s own hardscrabble upbringing (i.e., poverty, alcoholic and abusive stepfather) made the entry of chess into his life a beacon of light. It opened up an avenue to friendships, competition, erudition and self-confidence. At some point, he took up the role of managing chess in prisons for the English Chess Association. This would become a labor of love and a way to share his beloved pastime.

it is still a diamond.”

~Inmate

In the first couple of chapters, he lays out of the case for chess in terms of its benefits: decision-making, analytical skills, social development and mental health. He interviews John Healy a recovering alcoholic who spent 15 years in the “Grass Arena,” a park for homeless, vagrants and drug addicts. Healy talks about how he ended up in prison and learned chess through a chance encounter with a cellmate. It opened up the door to a mind darkened by alcoholism.

Portman also included a story about his visit to an unnamed prison in which he gave a simultaneous exhibition. He recounted the drab and depressing surroundings and mentioned the various briefings he received to ensure his safety. He was even told that the prisoners could use the chess pieces as weapons.

All of this to get chess into the prisons? It was to get him to appreciate where he was and who he would be dealing with. When the time came, the buoyancy in which the prisoners entered the room was something not seen in a long time.

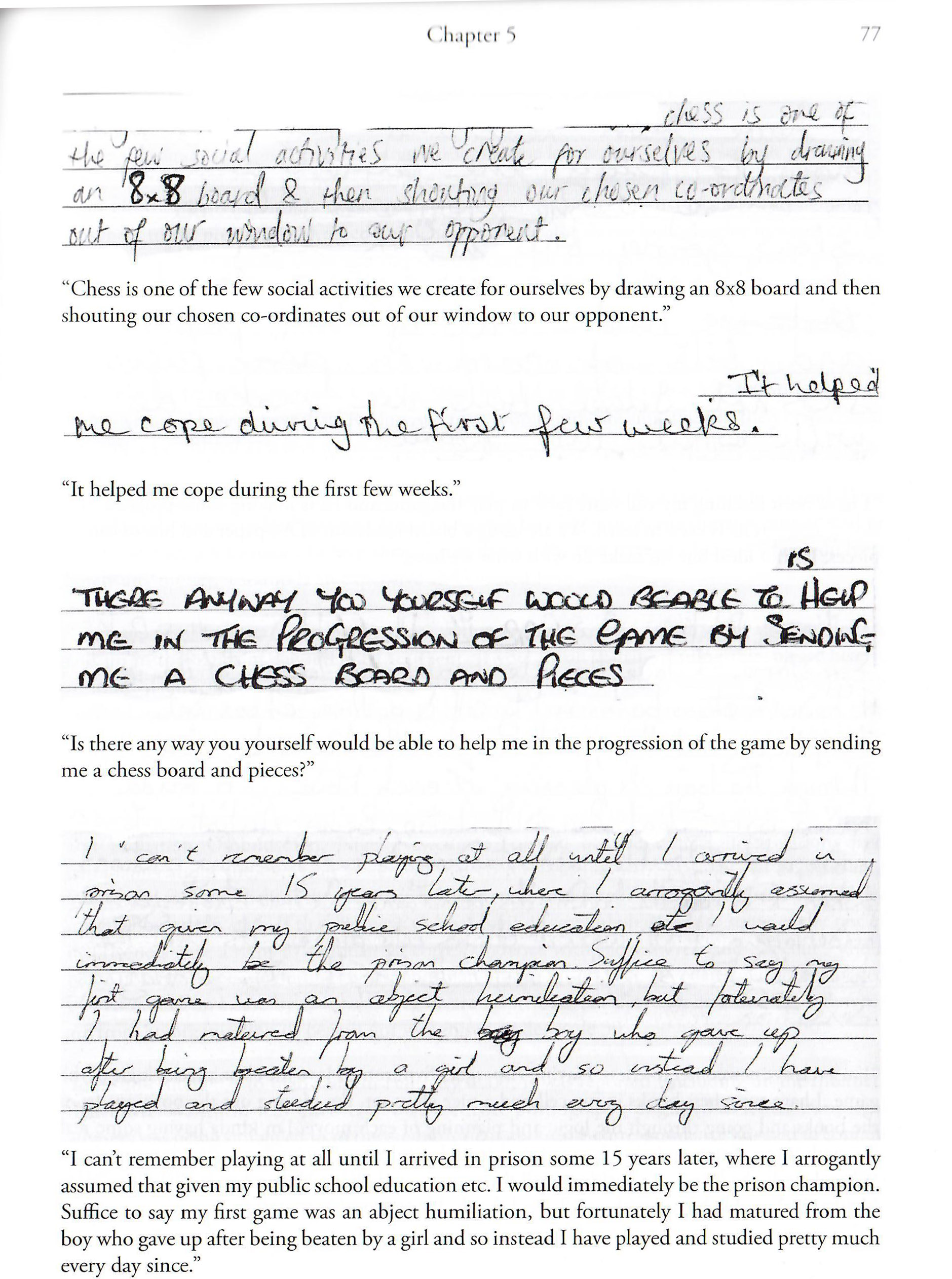

My favorite chapter is titled, “Testimony from Inmates.” It aptly includes excerpts of handwritten letters of prisoners. As one who often writes inmates, I do realize how important these interactions are. Every letter is probably read 20 times and each visit savored and every word digested.

After Portman’s auspicious visit, he drove home with a glow thinking that he had lit a spark. His visit and subsequent letters made a big impact! To get an idea, here are a few:

My rating is 1800 and was arrogant enough (before coming to prison) to suppose that I would be unbeaten in prison but I am being frequently humbled by some fellow inmates.

I did once spend 2 years carving a chess set out of matches.

…all the concerns I have to endure on a daily basis in prison are neutralized when I have a chess board in front of me, and so chess has proved to be a grate source of serenity and pleasure. It has also brought me quite literally out of my cell (shell” as when not playing chess I tend to keep very much to myself, but I have played and subsequently talked to a wide variety of prisoners of all colours and backgrounds whom I would otherwise have avoided like the plague.

…decent chess players in prison tend to command a certain degree of respect and be looked up to by other prisoners.

It helped me cope the first few weeks.

There are many more gems in Chapter 5 and the handwriting makes it much more intimate. The letter on pages 70-71 is a must-read!

Portman does not hold back in criticism of how some prisons deny prisoners access to materials. This has been an ongoing battle as prisons have to ensure the safety of the staff and the inmates. We all have heard of prisons having a problem with contraband items and suddenly there is a security issue when shanks, drugs, flammable substances and even homemade firearms are found! It certainly is a challenge. In one instance, I had to produce my organization’s ID number before they’d allow any materials in.

There certainly needs to be more of an effort at outreach to prisons. It would certainly be a positive activity and has been said to require a certain discipline in thinking. Portman includes a couple of the prisoner’s games in the back of the book which provides even more insight into the level of talent. He also includes instructional material, puzzles and some classic battles of the greats. Lastly, he provides some chess resources and recommendations.

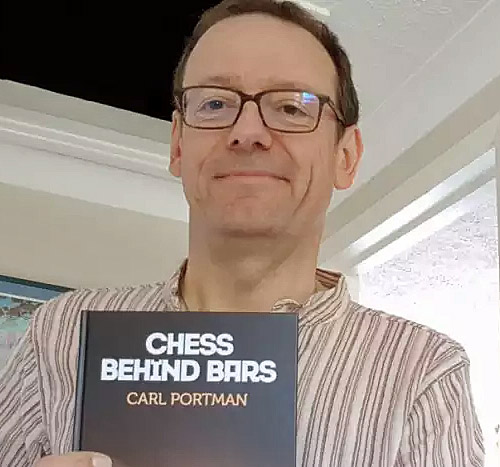

Carl Portman with Chess Behind Bars

The book had quite a few gold nuggets and even discusses the “Future of Chess in Prisons.” In this chapter, he entertains a discussion on what UK prison are and are not doing for their prisoners. Again, he promotes chess as a solution to some of the issues that plague prisons in terms of managing recalcitrant behavior. He also discusses mental health and provides a prescription…

“…every inmate (male and female) to be given the opportunity to play chess. For every prison to have a chess club and associated resources; for chess to be a component of the prison education curriculum; for chess to have prison certification and accreditation to enable inmates to prove their achievements upon release.”

He then lays out tasks for each actor in this effort from Prison Director to the inmate to those who simply want to help. I would recommend this book to any person who is involved in prison chess as a volunteer, as a prison worker or as one who may have a relative or friend incarcerated. It is a thoughtful book whose words will magnify the glory of chess.

Example of a handmade prison chess set

GM Kevin Spraggett weighed in saying that Portman’s book would “bring more ridicule to our noble game.” It’s ironic coming from someone who runs a chess site containing hundreds of pornographic images. It is disappointing that Spraggett crassly opines that the only captive market is for prisoners and that Portman’s prescription “wouldn’t amount to much.” He even adds that chess didn’t help prisoners from ending up in prison! Extremely bizarre logic from the legendary Canadian Grandmaster.

of the greatest possible value.”

~R.F. Green

Of course, Chess Behind Bars is not your usual chess book, but has quite a bit of practical value. I would agree that chess cannot help reform everyone and is certainly not a panacea for society’s social ills. There are countless stories of notable chess players whose minds were tormented by unsavory addictions and vile thoughts. However, chess has been proven to help those who seek to cope with the rigors of prison life, have aspirations for self-improvement, and develop a more refined approach to decision-making.

At the 2013 U.S. Chess Federation meeting, there was a report given by Sandra Guisso on prison chess in the Brazilian state of Espírito Santo.

The prison population is comprised primarily of 19-30 year old Afro-Brazilian men. They have run the program for the past 9 years, and in that time, prisoners were tasked with making chess sets/boards to sell, as well as learning how to play. Ms. Guisso said the program has 12 groups, each with 15 prisoners, who learn and play chess for 50 minutes, twice a week. Compared to the general prison population, participants in the program had a recidivism rate of just 27% (link).

If we are wise, we would heed to the advice of Portman by suggesting a larger role for chess in the prison system. The book makes a compelling case.

Link: https://www.qualitychess.co.uk/

Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Chess-Behind-Bars-Carl-Portman/dp/1784830321

Portman’s Thesis

https://londonchessconference.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/CarlPortman.pdf

American movie “Life of a King” was a testimonial based on the true story of once-imprisoned Eugene Brown. Portman’s thesis in the book adds support for how chess can be used to rehabilitate.

In general, how we can cooperate with your regarding chess education guides? (https://www.chesswizards.com)

Thanks!