After 2023 World Open, a new chess era unfolding

A few weeks ago, Fidel Corrales Jimenez won the 2023 World Open with an undefeated 7.5/9 beating out eight others (including GM Hans Niemann) by a half-point. A strong performance was put in by 17-year-old IM Justin Wang who earned a GM norm in the pack of players ending on 7/9. The World Open is the marquee event for chess in the U.S. running for more than 50 years.

Having established Philadelphia as its home, the event has moved from the Adams Mark to the Wyndham/Sheraton City Center Hotel to the iconic Marriott at Reading Terminal, the change of venue isn’t the only thing that has evolved. Is there still magic at the World Open?

Adams Mark Hotel, the longtime venue of the World Open. It was demolished in 2006.

“The playing site is a literal festival as players and their guests are milling about. The electricity can be felt from excitement. Many reunions are made between players who have not seen each other since the last World Open or perhaps many years. There is always smile, laughter and excitement… at least in the beginning of the tournament.“

~Daaim Shabazz, “The Magic of the World Open Chess Tournament” 13 July 2003

World Open in Perspective

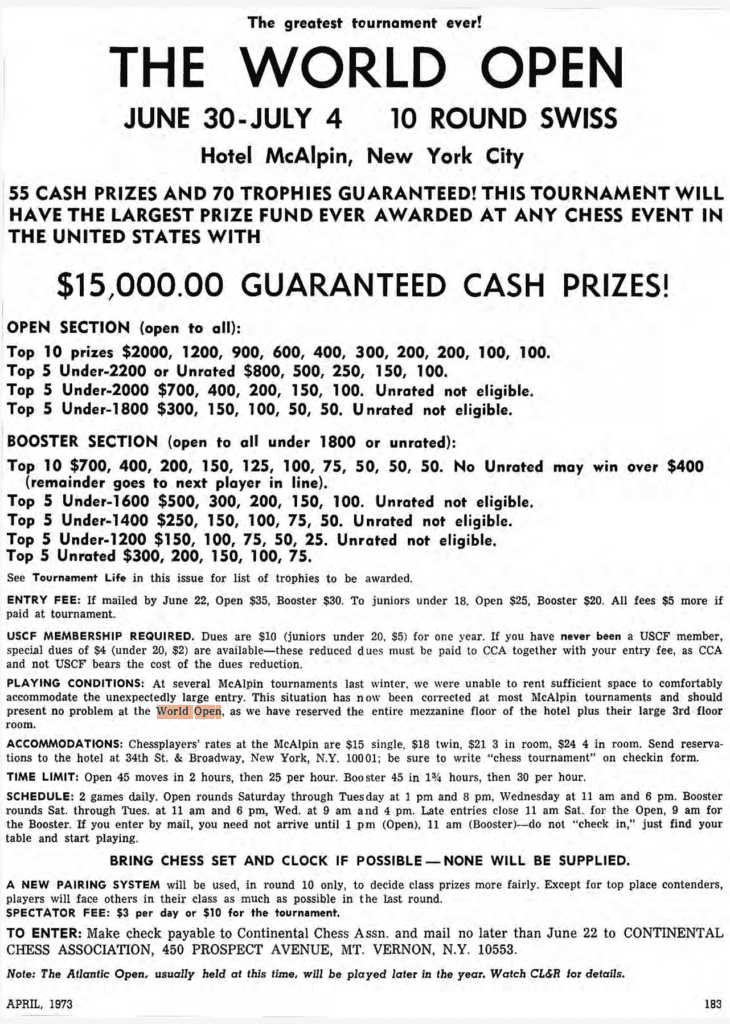

Founder of Continental Chess Association (CCA) Bill Goichberg billed the event as “the greatest tournament ever.” The 1st World Open tournament had its beginnings in 1973 in New York at the McAlpin Hotel during July 4th weekend. The event attracted 725 players to “The Big Apple,” for a $15,000 prize fund. Six-time U.S. Champion Walter Browne (then 24 years old) won with 9/10 and a first prize of $2000. According to the report in the September 1973 Chess Life, Bent Larsen won the next edition with 8½/9. Some of the other luminaries playing in the early days were Pal Benko, Anatoly Lein, Ron Henley, Florin Gheorghiu, John Fedorowicz, Yasser Seirawan, Tony Miles, and Arthur Bisguier.

Announcement for 1st World Open

In the 80s was a new crop of young stars with a few new Soviet veterans like Lev Alburt (Ukraine) and Roman Dzindzihashvili (Israel) who had emigrated in 1979. Dzindzi won the prestigious Lone Pine tournament and joint first at the World Open in 1980. He would become known in the New York area for his blitz exhibition (including giving ridiculous odds) and later his video series. America would become the beneficiary of techniques imported from the famous “Soviet School of Chess” thus influencing the next generation.

World Open: A Barometer of Talent

The young crop of young stars dotting the World Open tournament included young stars like Joel Benjamin. Unfortunately young players like Michael Wilder and later Patrick Wolff retired from chess before getting a taste of World Open victory. Benjamin recently co-authored with Harold Scott a book titled Winning the World Open narrating the tournament’s history. During these times, New Yorker (then-IM) Michael Rohde was joined by Soviet immigrant, Maxim Dlugy who would win the World Junior Open in 1980 and the World Open in 1985. Dlugy earned his GM title in 1986.

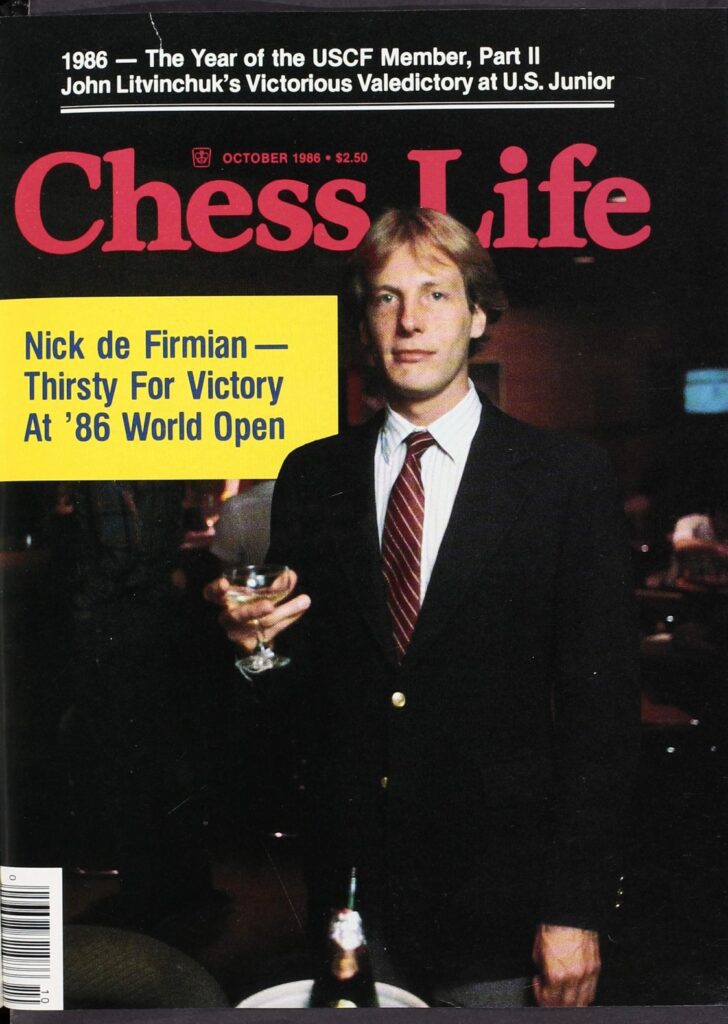

In the 80s, players such as Yasser Seirawan, John Fedorowicz, Nick deFirmian, Larry Christiansen, and Benjamin were challenged by an infusion of talent from the former Soviet Union. These American talents were products of the “Fischer Boom” and represented the future of American chess. Seirawan spent most of his esteemed professional career in Europe and played sparingly in open tournaments in the U.S. This included a few World Opens.

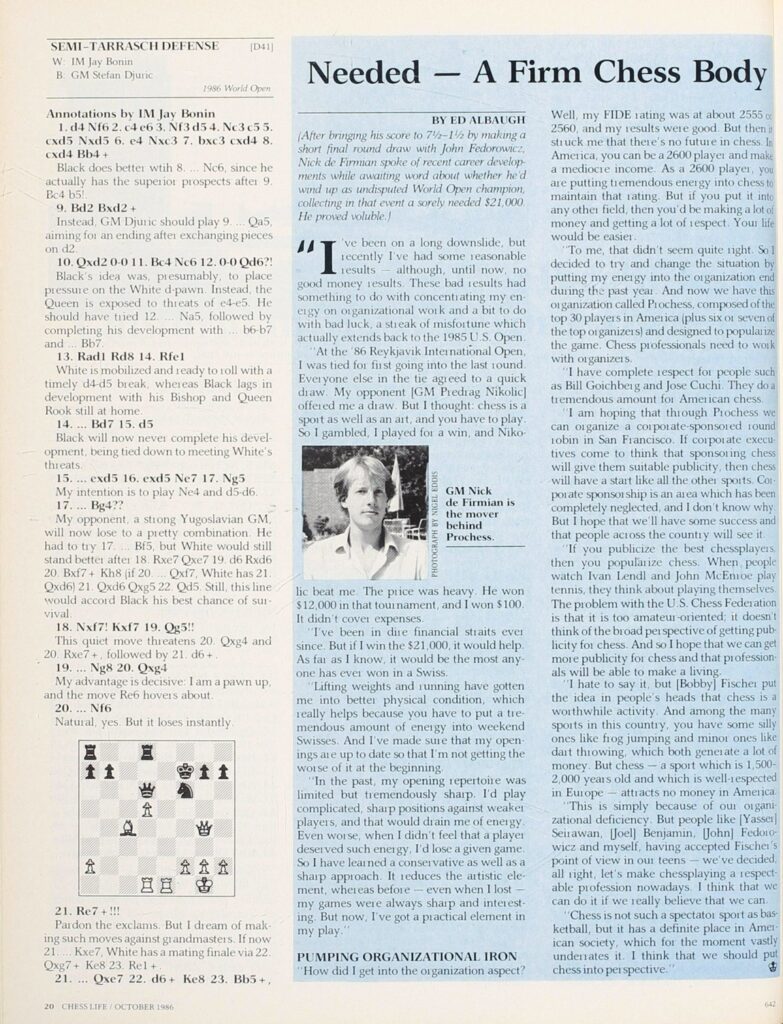

Below is the cover story with deFirmian winning a $21,000 first prize, but if you read his interview from almost 40 years ago, his words are still relevant when it comes to chess in the U.S.

“In America, you can be a 2600 player and make a mediocre income. As a 2600 players, you are putting tremendous energy into chess to maintain that rating. But if you put it into any other field, then you’d be making a lot of money and getting a lot of respect. Your life would be easier.”

~GM Nick deFirmian after the 1986 World Open

In the late 80s and the decade of the 90s, players such as Gata Kamsky, Alexander Yermolinsky, Alexander Shabalov, Alexander Goldin, Gregory Serper, Grigory Kaidanov, Alexander Fishbein, Leonid Yudasin, Dmitri Gurevich, and Sergey Kudrin established dominance of most of the top open U.S. tournaments. There are a few more Alexanders with Alexander Ivanov, Aleksander Wojtkiewicz and Alexander Fishbein getting in on the action.

Bear in mind, the U.S. had not produced many Grandmasters in the 90s. In the 2000s, there was still immigrant dominance, but it began to weaken in the late-2000s and early-2010s with the emergence of Hikaru Nakamura and a number of rising homegrown stars. The previous generation of immigrants had now become coaches and trainers. This gave the next generation access to professional training and also more chances to compete for norms. Meanwhile, the World Open still attracted curious players from abroad.

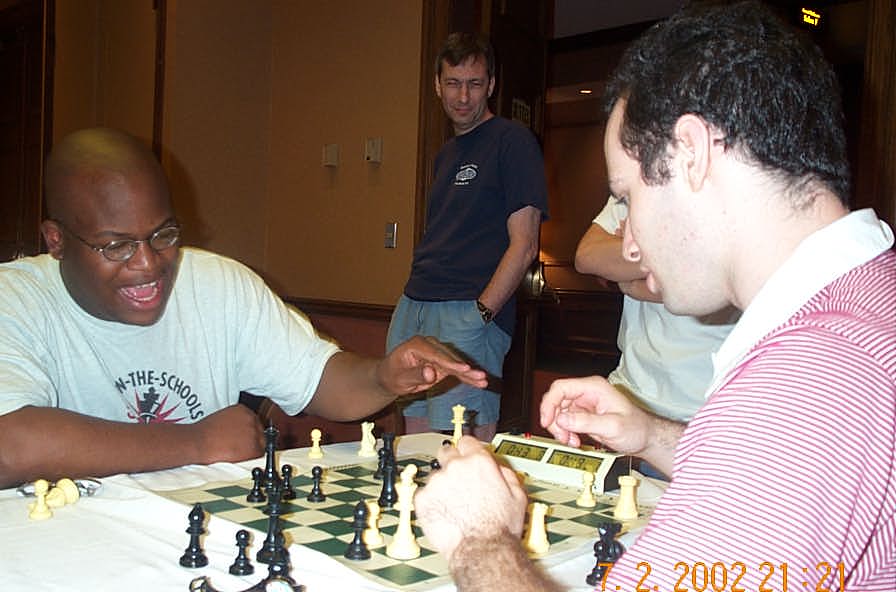

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Other international stars like Margeir Petursson (Iceland), Ian Rogers (Australia), Ilya Smirin (Israel), Michael Adams (England), Luke McShane (England), Loek van Wely (Netherlands), Johann Hjartarson (Iceland), Vladimir Akopian (Armenia), Jaan Ehlvest (Estonia), and Kamil Miton (Poland) also made trips to the U.S. to test the field. Evgeny Najer placed joint first three years in a row.

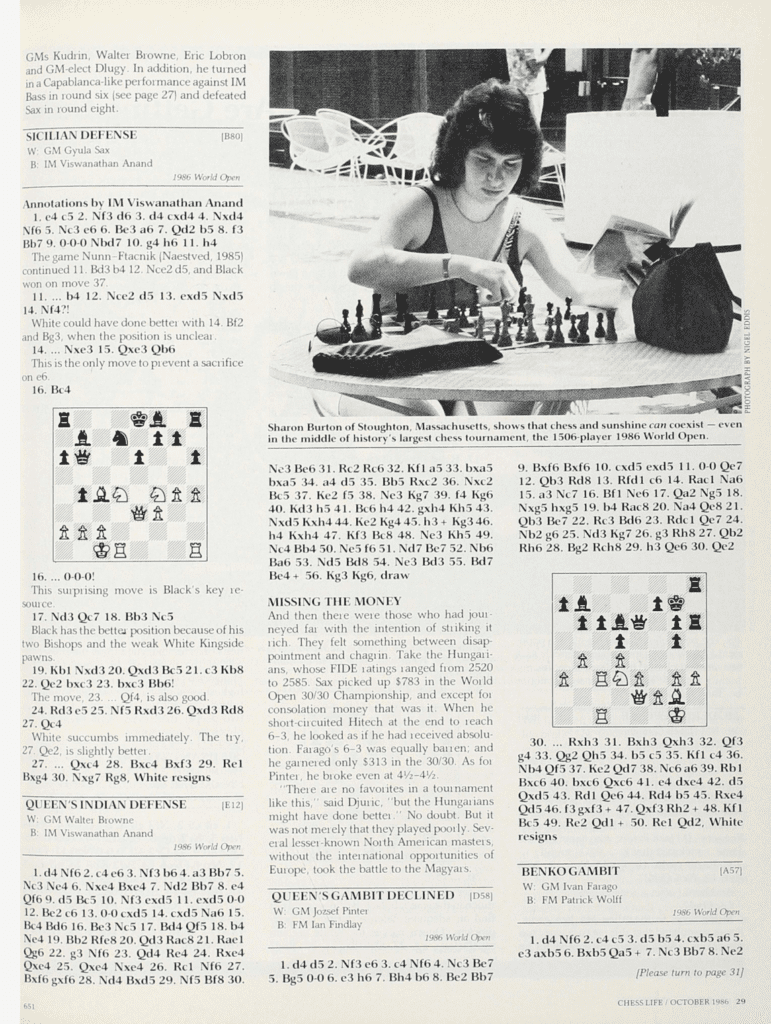

A little-known fact is that the 1986 World Open was attended by a little-known IM from India named Viswanathan Anand! The next year he would win the 1987 World Junior and become India’s first Grandmaster. Who would’ve known what he would become? In fact, he became a five-time World Champion and single-handedly lead his native India to become a top-five chess nation. He has turned out to be a model World Champion and global icon. Below are a couple of his games. His win against Gyula Sax is annotated.

This influx of international players had an interesting effect on American-bred talent in that there was a lot more competition. Thus, there was also motivation to improve or make a decision to devote time toward another endeavor.

The American stars of today who cut their teeth on open events have now joined the world elite. Hikaru Nakamura was one of the top professionals who continued to play at the World Open, tying for first with Najer in 2009. Nakamura, Fabiano Caruana, Sam Shankland, and Ray Robson made impressions at World Open tournaments and became gold medal Olympiad winners. All eclipsed 2700 with Caruana and Nakamura getting over 2800 and as high as #2 in the world.

A heavy dose of open tournaments is what has trademarked the American fighting style of chess as would be the case when you have to keep winning to stay in contention. At the World Open, 1/2-point could mean the difference between winning thousands, winning pocket change… or winning nothing! You are forced to fight.

World Open Conditions

The World Open is a fun tournament in one of America’s most iconic cities. With the exception of its home city of New York and a few stints in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and Arlington, Virginia, the tournament has traditionally attracted the country’s best and brightest talents to “Philly.”

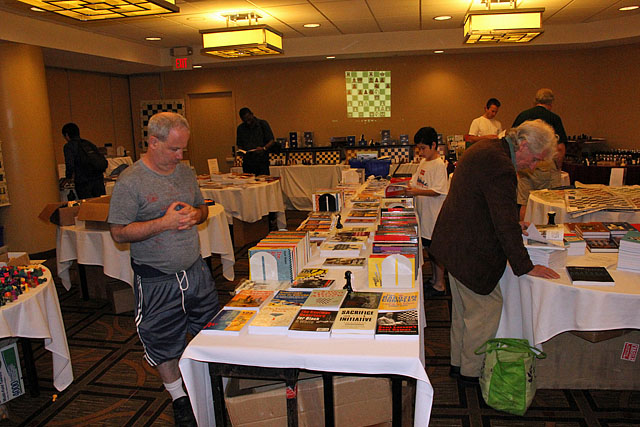

Scenes around World Open venues

Photos by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

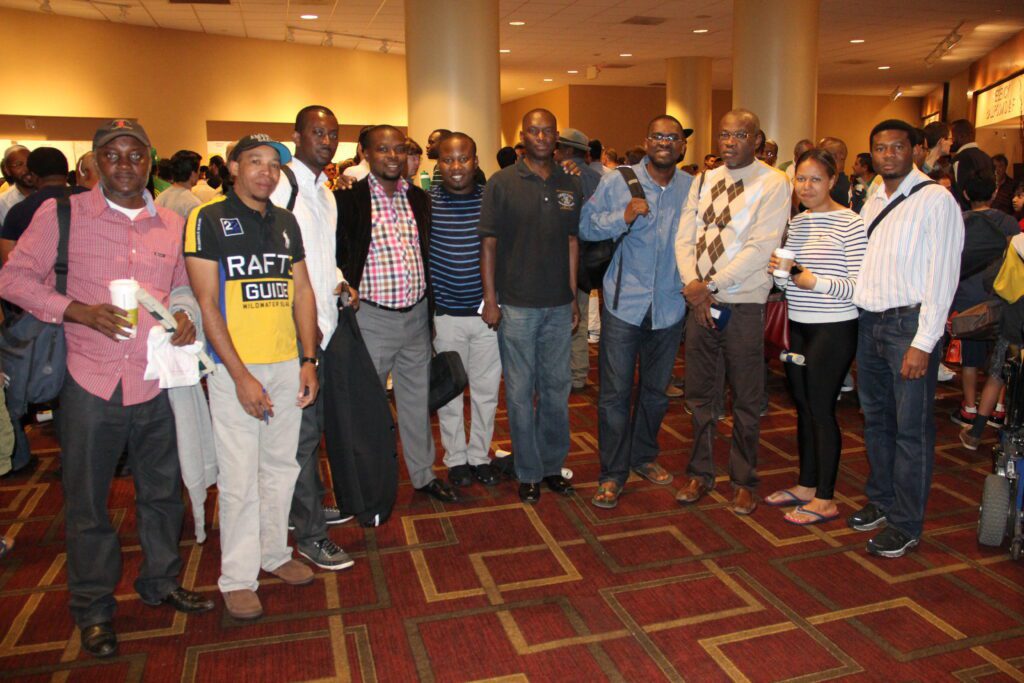

Until recently, we could always count on at least one top-100 player in the field. This is a tournament that once attracted world championship candidates. The World Open is less predictable than ever with many new faces every year. These players come from many parts of the world with serious ambition. There was the appearance of the Indian delegation for a few consecutive years when the country was beginning to show its might internationally.

As mentioned, the demographics have changed and the halls are dotted with a throng of parents and children running around with reckless abandon. Others are simply enjoying a chess picnic on the floor playing bughouse, blitz, or looking at games on the tablet. In other parts of the hall, you will find the infamous skittles room with many colorful blitz battles taking place.

The playing hall is generally massive and the pre-round buzz is palpable as people mill around waiting for the pairings that usually go up minutes before the round. The rush to find the boards doesn’t lessen the buzzing excitement and you hear people mention their opponent’s name and maybe the rating. Sometimes the player would even get an opening tip from a friend.

The Attraction of the World Open

Players assemble and of course, they take out their own boards, sets, and clocks and sit to wait for the opponent. Some players (particularly foreign) sit there waiting on a set as they are not used to carrying their own set. Nigerian IM Odion Aikhoje characterized the World Open as a festival or carnival atmosphere.

While he was impressed with the numbers, he stated that in Europe it is more of a professional environment focusing more on quality and not quantity. He also mentioned the number of young players. Interestingly enough, he mentioned losing to a 12-year-old Hans Moke Niemann in the 2015 blitz tournament. (Interview)

What has caused players to nix the World Open and choose international locations or local tournaments? Objectively, the tournament has had the same prize offerings over the years, but has added a number of interesting side events. If we look at the $200,000 prize fund (first reached in 1988), it has a range of consistency over the years, but CCA increased the fund to $358,000 in 2006.

It went back in the $200,000-$250,000 range but starting in 2015, CCA started making the prize fund guaranteed perhaps in the face of competition from the Millionaire Chess franchise, a novel tournament offering a guaranteed $1,000,000 prize fund. Then the COVID-induced Internet boom caused organizers nationwide to fight to retain over-the-board registrants. This shows how difficult it is to adapt to a changing market.

Certainly, the atmosphere has changed with the infusion of scholastic players in major open tournaments. Now there are throngs of parents in the lobby and in the tournament hall escorting their children to boards and supplying them with all types of snacks. This does create awkward moments when some of the younger players do not exhibit exemplary behavior such as clicking pens, fidgeting, eating full meals at the table, making all types of eating noises, sitting at the board in strange ways, parents hovering nearby, and scholastic players huddling by a friend’s board making faces.

On the other hand, it provides an interesting mix of competition and the World Open is an arena where dreams are formed. Many make the trip to Philadelphia to test themselves on the largest American stage for chess, with hopes of upsets, enhanced rating, and perhaps a norm. The World Open is an institution built by Bill Goichberg and has been a consistent presence for half a century. Goichberg has directed Bobby Fischer and has run some of the largest open tournaments in the country. For this long history and service to chess, he was inducted into the U.S. Chess Hall of Fame in 2018.

Outside Looking In

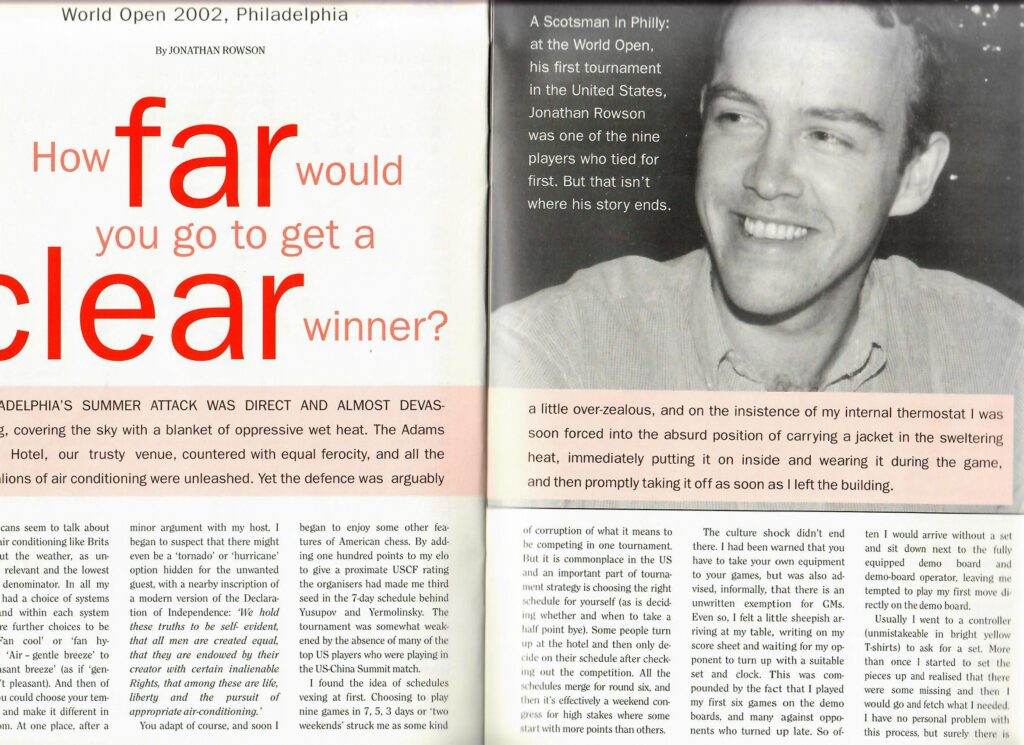

While there are many opinions about the World Open, it is certainly a tournament one has to attend at least once… or thrice. It has a certain type of excitement that other open tournaments do not have. One could view it as somewhat of a reunion while others may see it as a festival. Coupled with the holiday weekend, the tournament is a popular choice for a vacation, chess, or otherwise. Of course, there are some criticisms from those who may not have familiarity with the U.S. tournament scene. Jonathan Rowson of Scotland had biting comments about the World Open tournament in New in Chess (2002, 6).

Schedules

I found the idea of schedules vexing at first. Choosing to play nine games in 7, 5, 3 days or “two weekends” struck me as some kind of corruption of what it means to be competing in one tournament.

…

Some people turn up at the hotel and then only decide on their schedule after checking out the competition. All the schedule merge for round six and then it’s effectively a weekend congress for high stakes where some start with more points than others.

Equipment

I had been warned that you have to take your own equipment to your game, but was also advised informally, that there is an unwritten exemption for GMs. Even so, I felt a little sheepish arriving at my table, writing on my score sheet, and waiting for my opponent to turn up with a suitable set and clock.

…

So often I would arrive without a set and sit down next to the fully equipped demo board and demo board operator, leaving me tempted to play my first move directly on the demo board.

Pairings

Another peculiar feature of the World Open is that you don’t find out who you are playing until a few minutes before the game.

…

Now that schedules had merged I went for lunch expecting a “big guy” like Onischuk, Smirin, or Ehlvest in the afternoon. When I saw that I was playing IM Kamil Miton from Poland, with a relatively low USCF rating I thought I had been given a good opportunity to increase my score. This was an unskillful thought in all sorts of ways, but it is the direct result of having no time to check out your opponent before the game. It turns out that 18-year-old Kamil Miton is already a GM-elect with a FIDE rating over 2500 and is in the process of becoming even stronger.

Prizes

There was a pile of nine players on seven points. Each of us won almost $3500 but then our entry fee (GMs only pay the entry fee if they win a prize!) of $250 is subtracted from this amount. I find this a bit distasteful but I soon realized that such details are consistent with an event that is really an exercise in “chess capitalism”; most of the players and organizers are there to make money.

This is also par for the course in the U.S. and most people seem to accept the argument that entry fees from the lower events subsidize the (slightly) higher prizes in the top event and that these entry fees will only keep coming if prizes in the lower events are attractive.

This article was written more than 20 years ago but the same comments are made today by visiting players. Bear in mind the atmosphere is so much different in Europe with the one round per day standard, supplied equipment, and more formalized approach. In the U.S., chess is still considered an activity more for the weekend hobbyist than for the professional. Nick deFirmian emphasized a similar point in the aforementioned article written after his World Open win in 1986:

“The problem with the United States Chess Federation is that it is too amateur-oriented; it doesn’t think of the broad perspective of getting publicity for chess. And so I hope that we can get more publicity for chess and that professionals will be able to make a living.”

~GM Nick deFirmian after winning the 1986 World Open

Chess in the U.S. can also be very expensive (travel, hotel, food) and most times there are often no conditions provided for Grandmasters. There is only the entry fee waiver mentioned by Rowson. Imagine the expense of staying ten days for a one-round-a-day tournament in the U.S. It is prohibitive. There are only a handful of professional players in the U.S. and the sponsorship mentioned by Rowson in the article has not been easy to come by. Nevertheless, America’s flagship chess tournament continues.

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

at 2017 World Open where she had a breakout performance as a 17-year-old. She was in contention to win but drew the final round ending on 7/9 and GM norm.

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Despite critical comments about the American chess scene, the World Open continues to attract foreign players, perhaps out of curiosity. It certainly rings true to the name of the tournament. A literal “Who’s Who” of chess players have played and even shogi legend Yoshiru Habu has played. Interestingly enough, his participation went largely unnoticed, despite his status as an equivalent of any of the world chess champions whom we revere. I had a chance to chat with him (interview).

Photo by Daaim Shabazz

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Besides the Indians and Nigerians, there have also been a steady number of players from Latin America, most notably Cubans. Wesley So began playing while still representing the Philippines. He later attended Webster University and with so many others, attended universities with chess programs. These students flooded the World Open and gave the tournament even more strength. Programs like Webster and the University of Texas satellite campuses boast a wealth of international talent.

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Youth Movement at World Open

While the tournament is still exciting it no longer draws players from the upper echelon. It seems like a place where up-and-coming young players are in a feeding frenzy for rating points and norms. Upon first glance, half of the tournament competitors appear to be under the age of 21, a sharp departure from 20 years ago.

Looking at the world’s elite players (2700+ Elo) you see a cadre of players under 21. While up-and-coming players rely on closed tournaments for norms, players like Fabiano Caruana, Hikaru Nakamura, Ray Robson, and Jeffrey Xiong had to rely largely on open tournaments. Caruana moved to Europe for ten years to accelerate his growth.

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Photo: Ikuko Hardaway

This year, many of the juniors made an impact in the open section. The world’s youngest Grandmaster Abhimanyu Mishra in history was in the field and many other top juniors from North America. The other strong continent at the World Open was the college students. While not as young, many of them are attending American universities with chess programs. In fact, GM Srivatshav Peddi Rahul just earned his GM title and took a point from top-seeded Hans Niemann. The University of Texas-Dallas student had a strong outing.

The 2023 World Open was headlined by Niemann, a player besieged by controversy last year. Niemann recently had his lawsuit dismissed and it remains to be seen what further legal actions will be taken, if any. Nevertheless, one can admire his resilience in keeping his motivation after facing blistering condemnation worldwide.

Playing in these open tournaments may be his only option since all invitations have dried up after cheating accusations launched by then-World Champion Magnus Carlsen. He is the only top junior not playing in (or invited to) the World Cup. Alireza Firoujza declined his spot. The wildcards were given to two veterans (Peter Svidler and Vasyl Ivanchuk) who have enjoyed many World Cup opportunities in their lengthy careers. Nevertheless, Niemann was a big attraction and many viewers flooded onto various servers to watch his games.

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/ The Chess Drum

African Diaspora at World Open

The World Open seems to be a magical place for chess players from the African Diaspora. Most of the players typically come from the East Coast and the Midwest with many gunning for prizes typically in the under-2400, under-2200, and under-2000.

Today, young upstarts like Brewington Hardaway and Tani Adewumi are battling in the top section, replacing those who have passed away (Emory Tate), retired (Stephen Muhammad), or play infrequently. FM Norman Rogers fit in the latter category, but he was back this year facing a new era of young upstarts.

The World Open represented one of the few opportunities for Black players to earn norms and represented a successful arena for several players. The social atmosphere seemed to provide some motivation to perform well. The legendary Emory Tate enjoyed this tournament and used it as a stage for him to express chess in its ultimate artistic form. Here is some classic analysis of his win over IM Saljivus Bercys.

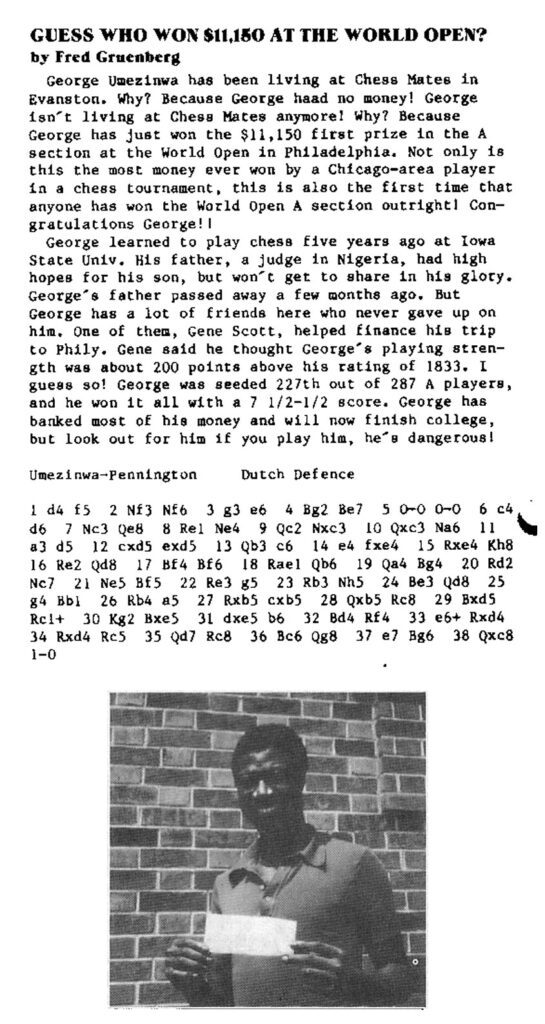

Black chess players have had breakthroughs at the World Opens. Some of the masters earning norms were Emory Tate, Stephen Muhammad, Norman Rogers, Farai Mandizha, William Morrison, Josh Colas, and more recent sensations such as Brewington Hardaway. Perhaps the most successful World Open player in the Black community was Muhammad. Not only did he enjoy the side blitz battles, but he always seem to carry away a bag of big wins over strong players. There are even some unheralded players like George Umezinwa who won the under-2000 ($11,150) and Barbados’ Philip Corbin who won under 2200, both at the 1985 World Open. Umezinwa later vaulted over 2400 and Corbin became a “Bajan” legend.

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Umezinwa’s story is certainly a World Open classic, but it is not as common as we would like to believe. In fact, there are many funny stories of “underrated” players and blitz hustlers thinking they can make the trip to Philly and clean up. Of course, blitz chess is so much different than classical chess and many of those aspirants went home disappointed. The World Open is not a place where you will simply show up and win. The blitz tactics that work in the park will often fail in the classical format.

The annual tournament is like a reunion of sorts and players would see players they hadn’t seen in their since the previous year. Emory Tate used to be a main attraction as his postmortem sessions were legendary. In my book, Triple Exclam!!! The Life and Games of Emory Tate, Chess Warrior, I opine that Emory was not just a chess player, but a chess performer. One unforgettable moment is the demonstration of his win over Sergey Kudrin… utter devastation and an even better dramatic portrayal.

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

I personally remember the first World Open I attended. It was 1990 when I was interning at Time Warner in New York. I hitched a ride with Jerry Bibuld and Maurice Ashley and my mission in chess was about to change. Arriving at the Adams Mark, I was impressed at the collection of players, particularly those of African descent that I had only read about. It would be the only time I would meet Wilbert Paige and lay my eyes on Alfred Blake Carlin. With Paige, I shared with him my marketing plan for a chess network for Black chess players. With Carlin, I would later come to his aid after he lost everything during Hurricane Katrina.

The Skittles Room

One of the big attractions of the World Open is the side action in the skittles room. When you walk in, you will see any number of people engaging in various activities including backgammon and cards. More common was the various blitz battle breaking out all over the room. Some of the chess hustlers would drive to Philadelphia for the weekend just to find a “customer”.

All of the “blitz demons” seem to show up with a constant buzz, trash-talking, and side bets. Sometimes the action was friendly, but no less exciting. In this match, between Zambia’s GM Amon Simutowe and Cuba’s IM Dionisio Aldama, a kibitzer almost causes a riot.

Then there was a matchup between IM Farai Mandizha and IM Emory Tate… an outstanding game!

Video by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Some may remember German Grandmaster Roland Schmaltz the original king of bullet chess and four-time world champion. Bullet has come a long way since then and there was recently a Bullet World Championship won by Nakamura who beat Magnus Carlsen. Schmaltz is now into the poker circuit while the online platform has gained a lot of bullet enthusiasts.

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Corbblah is always reserved when he plays blitz… hard to get him to say anything. 🙂

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Photo by Daaim Shabazz/The Chess Drum

Such an electric environment… and then there was nothing. This was the morning after the World Open had ended. It’s just an empty room, but it held so many memories.

What’s next?

There has been a transition from the World Open as a tournament for professionals to a tournament festival for young, opportunistic norm seekers. Before the big draw was the prize fund, but now that there are more opportunities to earn norms and titles, young aspiring players are hunting for GM and IM scalps… and are getting them! The field is considerably younger with more ethnic diversity. There needs to be an improvement on the aforementioned issues. The same criticisms that Rowson (and others) mentioned still exist today. The tournament setting could use an upgrade.

More top-level professional players nix the World Open not only due to a more lucrative professional circuit in other countries but also to avoid being fodder for up-and-coming junior players hungry for norms and Elo points. Gone are the days a veteran GM can simply show up and collect a point. Alexander Shabalov was once the king of open tournaments for many years winning his games in brilliant style. However, he noticed a shift at the end of his reign and he had to adjust his style.

“You can’t play this way anymore. You can’t bluff a computer. Everybody works with a computer now, and defense techniques are so improved. It’s no wonder that my peak came at a time when computers were not strong yet.”

~Alexander Shabalov

I had written a piece on the World Open where IM Marc Esserman was showing his game against Awonder Liang and how he marveled at the young star’s defensive resourcefulness. Yes… it is getting harder to win since everyone has access to strong engines and training aides. We have reached a new era where the World Open is dominated by the youth.

I recall hearing a story about Arthur Bisguier playing in one of the open tournaments. Bisguier was USCF-rated only in the 2200s at the time, so his young opponent quizzically asked him if he was really a Grandmaster. He said in an embarrassed way, “I used to be.” Many of these young players have no idea of the legends who walked these halls before them.

What’s clear is that the World Open franchise has given us plenty of enjoyment and opportunity. We have made life-long friends, established business ties, earned norms for titles, and may have even won a prize or two. One discussion that comes up from time to time is what will happen when and if Goichberg decides to retire. Will he pass the baton on? Will he sell the CCA? In my own opinion, it would be a worthy investment.

There is still a market for over-the-board chess and if the pandemic has taught us anything, it is that online chess can never totally replace the social experience one gets from attending a tournament such as the World Open. In the online arena, there are too many other options which means it is hard to establish a brand distinction. However, there is a benefit of playing without the hassles of travel. Even with the savings, the experience is not the same.

Playing chess online will not make it alone, but serve as a strong complement to over-the-board play. I have attended around 20 World Open tournaments and what I enjoy the most is the excitement of competition, being able to watch, and interact with top players, reuniting with chess friends and associates, and getting a chance to walk around Philadelphia, a city I have come to appreciate. We are in a new chess era, so let’s enjoy the World Open each year and appreciate it for what it has given us.

Tournament Website: https://chessevents.com/worldopen/World Open (Drum Coverage): 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005, 2004, 2003, 2002, 2001